Kisi Ke Waade Pe Kyun

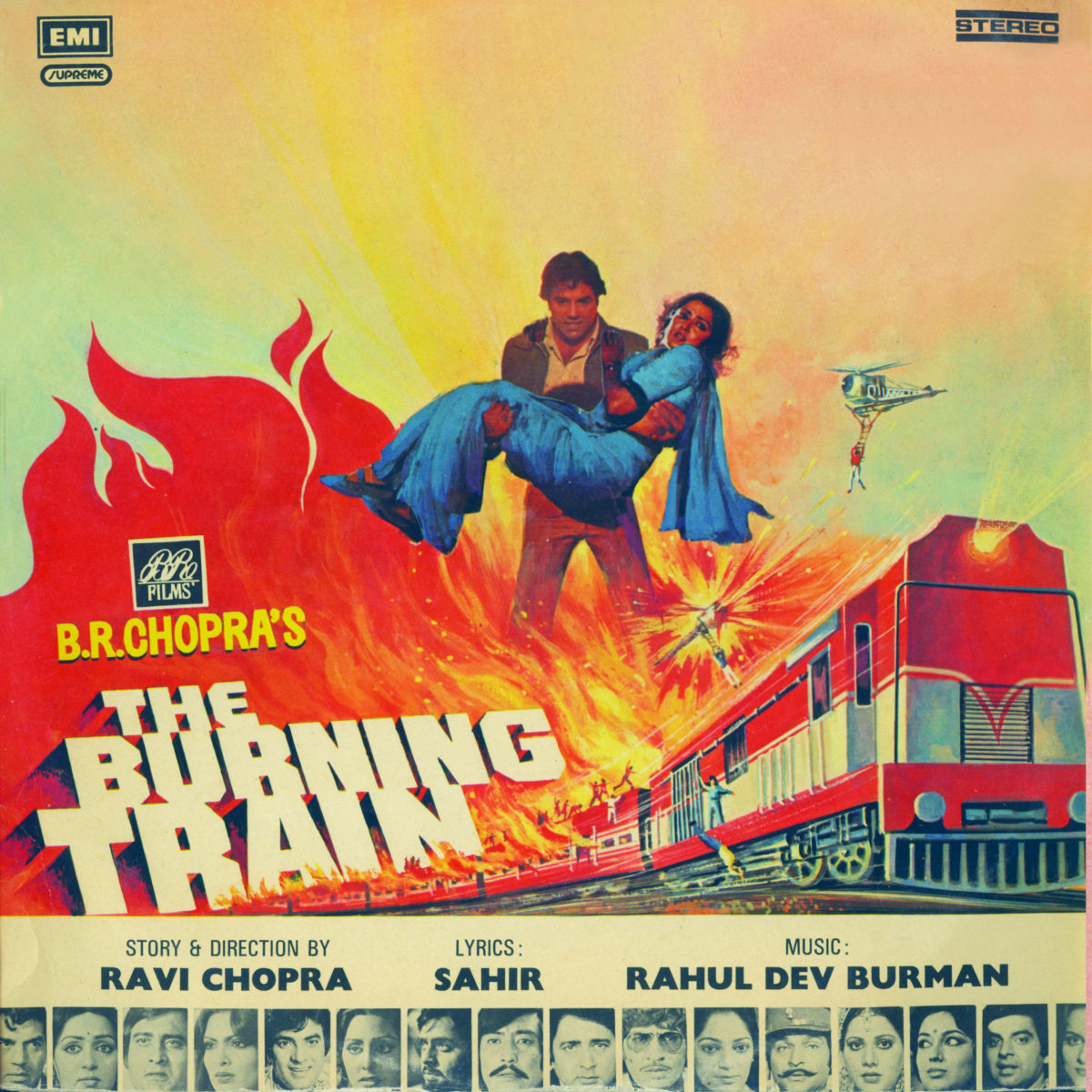

Film: The Burning Train (1980)

Producer: B. R. Chopra

Director: Ravi Chopra

Lyricist: Sahir

Singer: Asha Bhosale

I hold it true, whate’er befall;

I feel it, when I sorrow most;

’tis better to have loved and lost

than never to have loved at all. – Alfred Lord Tennyson

The theme of a lover’s betrayal is a playwright’s favourite. Ever since the earliest acts, the stab of unrequited love has led forlorn, bleeding hearts to wander the grim environs of society’s underbelly in wretched hopelessness and restless anguish, searching a solace never easily found. It is an emotion that forever clings to the heart, like moss growing on the damp walls of a decaying building. And yet the disowned lover strangely clings back with a greater fervour, knowing all the while the futility thereof but hoping against hope, unable either to suppress the emotion or surpass it…

The somewhat escapist world of commercial Bollywood cinema empathises a great deal with the spurned lover – especially of the male variety – who is allowed frequent access to a bottle of wine and a fall into the stray arms of a transitory relationship.

Many a male protagonist – when thus in disgrace with fortune – has dragged his feet up the dimly lit, all-embracing steps of a “kotha”, that decrepit house of disrepute and den of immorality which lies beyond the proverbial veil guarding society’s honour. It is here that he is administered the soul medicine of music with liberal doses of philosophy by the “tawaaif” (strictly speaking, a female courtesan in days of royalty, or a trained singer/dancer of classical/folk/ghazal lineage), who, like a halfway-house to reform stationed on the fringes of civilized society, puts the derailed lives of others back on track – only to never be allowed one of her own.

And so too, did a wronged Ashok (portrayed by the handsomely featured Dharmendra) from the multi-starrer blockbuster “The Burning Train” hurl himself into the arms of a tawaaif, reaching out for solace on being betrayed in love by Seema (Hema Malini). He was indeed fortunate, for the musical balm was provided by one of the finest mujaras ever – “Kisi Ke Waade Pe Kyun” – a masterpiece in the ghazal genre composed by the one and only Pancham, written scathingly by the deeply sensitive Saahir and sung devilishly by an Asha who delivers a stunningly incandescent performance!

In The Burning Train, Pancham, a man of limitless oeuvre and impossible range who commanded a mastery over every flavour of music, has probably even by his lofty standards delivered an album so blazing, the spool would probably burn on playing just the title track – a quirky, throbbing heavy metal masterpiece so unusual, it ranks among the very best pieces of experimental music to this day. Complete with lush love songs, an Indo-Western dance number that changes colour faster than a chameleon, a children’s prayer that tugs at the heart-strings and a zesty qawwali which escapes its orbit to merge with heavy Western brass sounds only to fall right back into place at the drop of a hat, The Burning Train soundtrack is one of those rare works of magic without parallel in the musical universe, that only and only a Pancham was capable of. On this impressive backdrop, and especially being cruelly edited out of the film, “Kisi Ke Waade Pe” is a mujara with a difference – not a finger-snapping, foot-tapping whirl of sound that captures the imagination instantly, but one that grows on the listener, maturing with the years and like all R D songs, increasing miraculously in melody with the passage of time.

A mujara has to have a “live” feel to it and focuses on “gaayaki”, requiring a capable singer of stringent discipline and learning to do it justice. The sarangi may accentuate the pathos and the tabla may keep pace with the nimble feet of the dancer, but a standout performance demands the command of a singer’s voice.

With his trump card Asha at his disposal, Pancham based this song on a classical backdrop and infused it with the harkats, taans and murkis typical of a Hindustani dance number. With the humble Marutirao Keer helming the rhythm, Pancham had the country’s finest ever percussionist/arranger by his side – the tabla in this song itself is adequate testimony to this fact!! Saahir, forever the enigmatic poet with the common touch, was perhaps just the man to write a ghazal with enough philosophical depth for a colossus like Pancham to wade in. Together as a team – and on individual brilliance – they delivered a song for the ages.

With the aalaap itself, you notice the marked deviation in Asha’s voice. It is instantly recognizable, but sharper in inflection, louder in pitch and edgier in its tone (a hat doffed to Parveen Sultana perhaps?). Asha simply owns this song!! Cutting through it with raw energy like a scythe, precise at the points of emphasis, she keeps you restless and makes every single word count. So beautifully timed are her pauses and so correctly arrested the slightly elongated taans and variations that not once does she let the song out of her grasp. Weaving and ducking through the tight knit of the complex composition without once losing breath or bending the tune to her convenience, she embodies utter mastery. Despite all this she seems to sing with an easy abandon, as if no phrase ever made could challenge her scale, as if making her way through the complicated weave of the song is akin to singing an everyday lullaby. So instantly does she stamp her authority not just on this ghazal but the genre itself that one wonders if film music’s gain was an equally great loss to the world of classical music…

A fast prelude on percussion, a short pause, and the aalaap pull you in… As the singing gathers pace, the astonishingly simple yet profound words roll out. Written a touch in anger and a touch in self-reproach, the bitter-sweet words of Saahir wound you… Three lovely couplets make up the antaras, in which the first line of each, sung in 2 portions, first pinches and then hits hard with stark realism… But the coup de grace is provided by the second line, which also makes the crossover to the mukhada. Rarely would a lover so beautifully express his/her loss thus:

Na wo hamaare hue,

Aur na hum rahey apne…

Mohabbaton kaa ajab, kaarobaar humne kiyaa…

Saahir, the disenchanted poet with his back to the world, encapsulates the futility of whole-heartedly loving an unfaithful companion with a subtlety and class that elevates the song above an ordinary mujara and assigns to it the status of great poetry.

Finally, and arguably above all, it is Pancham who gives the song its vintage! Crafting each note intricately with the dedication of a skilled artisan, he produces a resonating sound of such complex quality and authenticity that you get the actual feel of a live indoor performance being played right in front of your eyes…

Doing full justice to Saahir’s poetry, he goes beyond simply fitting the words into meter and adjusts the tune to express the feel of the lyrics. It is interesting to note how each antara is constructed, and you will notice the first line being sung twice – very ghazal like, in anticipation of what is to come next. The first time it is sung full-throated, as Asha effortlessly scales the high notes. Midway through the repeat recital of the same line though the singer seems suddenly to realise her predicament and drops in scale, singing more mutedly as though to herself in realization, making the words sigh as if and yielding a cutting edge to the irony of her situation.

With his excellently trained ear and penchant for classical music, Pancham has been completely at home when it comes to composing the traditional mujara-style numbers, and here too, brings all the required tools to the table. Somewhat “Mehbooba”esque in treatment or even reminiscent slightly of the fast “kathak” dance numbers in Kinaara, the song offers a throwback to the past and invites visions of the glory days of Hindustani culture that once patronized and nurtured the finer arts. The percussion flies in all directions as the tabla, like parched earth welcoming the first rains, revels in the lightning bolts of the player’s adroit fingers as they literally scorch the membrane and the ghungroos keep pace with the breathless beat… The sitar is played beautifully and intelligently fused with bells to resound in your conscience… and the saarangi weeps with dignified intensity, conveying anguish as beautifully as – if not more than – the singing.

The entire recording testifies to Pancham’s technical brilliance, and each instrument speaks its heart out, be it the thunderous sounds of the tabla or the slightly “distant” chorus of the violins. Actually, the violins seem recorded on another track, giving the sound a slightly eerie feel of emanating from afar. Again a masterpiece of Pancham’s imagination – for so high and so deftly do the violins fly, they seem to belong to some other time deep in the past, colliding with the high stone arches of a bygone royal “haveli” and cascading down to make those long forgotten tombs of Hindustani music come alive with a sigh as the galleries, pillars and creaking stairs resonate to the art they once patronized… So bewilderingly authentic is the feel those violins impart that you achieve a virtual walkthrough through a forgotten past, and are reminded of a time when the “tawaaif” was not just a degenerate in the eyes of society, but rather a gifted artist in her own right. How beautifully Pancham captures the “tadap” or slow poison of her singing and administers it to you, leaving you to writhe in sweet agony long after those violin strains have left your ears…

Cocooned by the silk of Pancham’s music, you feel haunted even days after physically laying it down… it still plays within the walls of your mind – you are possessed again by the man who never left you…

Promises will continue to be broken, and art will continue to serenade broken hearts… but one promise will forever remain unbroken – never again will a Pancham walk the earth, never again will someone so possess our collective souls…

Shirish Prabhudesai

panchammagic.org