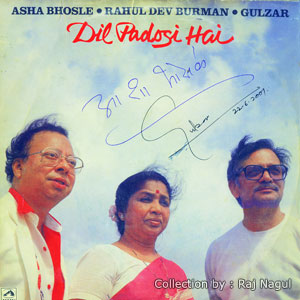

Joothe Tere Nain

Album: Dil Padosi Hai (1987)

Lyrics: Gulzar

Singer: Asha Bhosale

An enchanting enigma – “Joothe tere nain” (Dil Padosi Hai

First, this is not an oft-heard song, or melody that the hoi polloi would even attempt to hum. Nor can this gem of Pancham be ever relegated to the delimited domains of bathroom-singing, or, even to the dilettantes of classical music! This is a pristine classic that just needs to be listened to, not just heard! In other words, if you want to enjoy every fiber of this composition, lay down your tools (if you are working), or your ladles and spoons (if you are cooking), or best, simply abandon any other activity that besmirches the attention that this great work needs!

No wonder Pancham, even during his direst and unrewarding span of life, inherently believed that his creativity is best left to a very private and dedicated audience, which luckily for the die-hard fans of R.D.Burman, burgeoned as an album! Add to this fact, that thisoneofthemanymagnumopuses woven by Pancham’s baton was supported by two stalwarts − one to describe the subtlest emotions and imaginations in black and white (Gulzar, the esoteric poet), and one to render it (Asha Bhosle, the gifted muse) in the colors painted by the maestro to fill the canvas that can only bespeak of the genius behind the creation – the one and only Pancham!

My penchant efforts to glean more information about this song from the WWW proved extremely unfruitful (all the Googling left me only exasperated) and, in a way, I am happy that it left me to my own analysis and conclusions. The implicit disclaimer here is that my analysis of this masterpiece is entirely based on my limited knowledge of music (a vast ocean in itself), and is therefore subject to question and scrutiny. Anyone who can kindly provide a better analysis (with technical references, and appropriate elucidations of the statements presented) of this song simply overrides my observations.

It indeed was a travesty of categorization when I found that the songs of Dil Padosi Hai on one of the premier musical sites are stored under: Urdu (Ummm…I shall give a breather, maybe) -> Ghazals (eh?). That said, while you find a song like “Raat Christmas ki thi” shoved under the Ghazal category, you can understand, how deep the understanding of the musical genre by the general populace is!

It is as if I were living on a different planet when I kept hearing the song (again, and again…). To write my humble treatise on this subject, I need to come back to earth and share my findings (however erroneous they are)…

Because the remarkable fact about this creative work is based on rhythmic extravaganza (as is true of Pancham’s genius with taal-shastra and his own improvisations with the established norms (the inimitable, creative, and maverick that he was…), I shall attempt to share with you some of myown (even if skewed) observations.

To me, when I (in an infinite kind of loop) started analyzing the beat structure, I found that the song starts with a short alaapencapsulated within an ambient environment. Then, a short 5-beat (in terms of quarter beats) minor–chord phrase that can confuse folks. This is followed byAsha’s take on the mukhda. Before I discuss further, I want to share (oh! not again!) my few thoughts… First, let me put down a few facts about a couple of taals that intrigued me, which my observations anchor upon. One is called the Shikhar taal whose elemental structure is based on a 17-beat cycle. Pardon me for digressing here, but if you visit the Wikipedia, it has a structure for this taal defined as: 17 = 6 + 6 + 2 + 3. My traditional book on Tabla Ank has a different structure as mentioned below:

|

Shikhar Taal (17 counts), 4 beats |

||||||||||

|

Bol |

||||||||||

|

X |

2 |

|||||||||

|

dhA |

trik |

dhin |

nak |

tungA |

dhin |

nak |

dhum |

kiTa |

taka |

dhet |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

|

3 |

4 |

|||||||||

|

dhA |

(r) |

(r) |

( r) |

thiTa |

kata |

(r) |

gadi |

(r) |

gan |

tA |

|

12 |

X |

x |

x |

13 |

14 |

x |

15 |

x |

16 |

17 |

Note: I have added the (r) as part of a rest in Western music where nothing is played but involved in the total number accrued! X is called sam − the point of time the first beat in the cycle starts (also called the leading or main beat).

And there is also the Vishnu taal (a secondary version), which can be depicted as:

|

Vishnu Taal (Second Version) – (17 counts), 6 beats |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Bol |

|||||||||||||||||

|

X |

|||||||||||||||||

|

dhA |

( r ) |

ki |

Ti |

ta |

ka |

dhu |

ma |

ki |

Ti |

ta |

ka |

ghe |

( r) |

dhi |

na |

tA |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

There are other taal structures in Hindustani music that also comprise 17 matras (or tokens of the overall counting part of the beatstructure) but that is beyond the scope of this discussion. Second, my restriction to just the above two has the following distinct reasons:

-

Both comprise 17 beats (quarter notes).

-

Vishnu taal has a 6-beat structure that mightappear to closely adhere to the song’s beat structure because of the movement.

-

I lean toward the Shikhar taal more because the song starts on a 5-beat segment (the one discussed already in the paragraph above).

The actual song’s mukhda(or the beginning phrase of a composition in terms of lyrics) starts on the 6.5 beat (off beat after the sixth beat/stroke) and then continues till we count 17 beats in succession (as a gentle reminder, do not count from 1 through 17 in any language; if English, count from 1 through 9, followed by 1 through 8. Why? Simply because after 10, the pronunciation of the numbers 11 through 17 involves more than one syllable and, therefore, can induce errors in the strict timeslot in which one has to count the beat or the timesignature), and the second utterance of “Joothe…” will again fall on 1.5 of the count-structure of the second cycle. Now what happened to the first five borrowed beats? Pancham seems to returnthoseat the end of the first antara in a quick roll on the tabla for 5beats, so as to maintain the mathematical equilibrium − one of the divine aspects of music!

You might also observe that while the “Joothe…” part is rendered, there is no maracas (which Pancham predominantly uses to embellish the beatstructure, now offbeat, now on the sam(let us call it synchronized for want of any other word), but when Asha gets into the antara, the cycle turns out to be a straightforward 8-beat cycle, and the maracas goes chik-chik chik-chik (r) chik or 1-2-3-4(rest) -5 (the last chik sound) and the tambourine adds a delectable off–beat sound at the 8.5 beat). Now this urges me to add a few more comments…

While my focus was on the Shikhartaal structure, I would wade through the gazillions of pages and find one very interesting article as presented by one Girija Rajendran who had interviewed Asha (as part of the Screen magazine interview). In that interview, Ashaquotes almost as an aside, about Pancham’s intrinsic knowledge of the rhythm and his experimentations evident in this song on an 8.5–beat structure. It is no rocketscience to infer that 2 x 8.5 = 17! WasPancham “de-normalizing” (sorry to use a database management term − bad habits die hard!) this fairly unplayed taal, to segments of everyone’s comfort zone of the 8-beat cycle, and leaving the prowess of the singer to pick up the cue at the right beat (quarter/eighth) as an act of condescension for the rest of the world to come to histerms?

In other words, the 8.5 (or 17) cycle is transparent to the endlistener (a new nomenclature based on the “enduser” paradigm), and even if the listener taps to the 8-beat structure, he or she still finds a comfortable abstraction of the synchrony involved.

Note: There are advocates who have their own enunciations as to the structure being a combo of 8 + 9, but in my opinion, a rhythm structure (layout) is strictly mathematical in that the count devised should end up in a clean sum (hence the 8.5 structure that I think is more amenable to mathematics)! I have not heard of any rhythm that goes with one set of count one way and turn higher/lower in the other!!! This is the distinguishing factor between taal and raaga (where the aaroh and avaroh can comprise different sets of notes (in number) but not thetaal!)

Now let us look at the melodic part of the song:

The lively take-off of the alaap itself beckons you with an intimate message: this is not a beaten-track raaga! The sonorous mellifluence symbolizes one of the least–used raagas − Patdeep. The nearest equivalent of this dusk-time raaga in Karnatik music is Gowrimanohari. Another oft-used raaga Keeravani (originally a Karnatik raaga) has been adapted into the Hindustani mainstream and has many Bollywood songs to its credit. The structure of Raaga Patdeepis:

Aaroh: SRgMPDNS

Avaroh: SNDPMgRS

Note that the “ga” is KomalGandhar (Eb/D#).

Note: This analysis is portrayed on the Cm scale (if you go by the original song, it would be on the Dm scale (as corroborated by my musician friend Ajit Iyer).

The predominant but minimal ensemble used in the whole song is limited to a delectable subset, comprising the santoor, flute, soprano cello, an unobtrusive keyboard, and the reigning percussion − tabla! Though I could go phrase by phrase, (or worse, note by note) of the interludes, it suffices it to reiterate just this: the antaras are the familiar 8-beat based (as evidently the transformed beat styles of the tabla as it goes racy into a Keherwa style, or for the displeased, one can simply extend the beat structure to teen-taal(but halving the time cycle), sans the bol structure.

My emphasis is simply on the time-signature under consideration (half-beat or quarter, which makes the palette different in the outlook of appreciation).

As a fillip to the wonderful audience that appreciates good music (ahem!), like Pancham’s, a good comparison for you to familiarize with the “Oh-yes-that” feeling, compare the raaga of this song to the one (if you have…) you have heard in a song of yesteryears – “Meghachhaye aadhI raat”(a song, I am sure composed by Dada Burman, but the arrangement done by none other than his prodigal son – Pancham – look at the play of rhythm in the interludes that uses a ¾ beat structure in the Roopak taal base…Sigh! This goes on and on…).

The intricate way that Pancham has played around with established norms of classical music and yet conformed to the rules of mathematics (that music strongly represents) is the highlight of this wonderful song. Should you need an ecstatic moment for yourself, just hear the prominent but least heard (sort of oxymoronic) minor/major seventh chord (G#maj7 on the Cmscale that I started with, but would translate to BbMaj7 on the original scale of Dm; I am used to starting the easy, established and probably the lazy way of the C-based scales…, as corroborated again by my friend Ajit Iyer) that titillates your aural spectrum! Anything said more than this would be a waste of words!

God bless the one and only musical genius called Pancham!

Venky Subramaniam

panchammagic.org