Nodir Paare Uthchhey Dhowan

Song: Nodir Paare Uthchhey Dhowan

Album: Phire Elam (1986)

Lyricist: Swapan Chakravarty

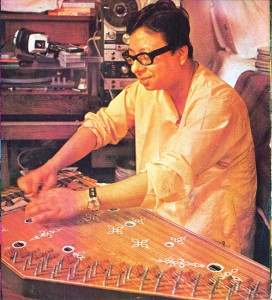

Singer: R. D. Burman

The basic Bangla (Bangla adhunik gaan) songs of Rahul Dev Burman, or Pancham, often tell us short, simple stories, mostly of simple folk, their loves, their lives. Be it a train journey with kids, teaching them the Bangla alphabet, or a village guy buying a tangail sari for his bride, or a village girl talking to her bird about her love. In films, the situations would be mostly formulaic, and did not always allow a composer to experiment (although we know what experiments Pancham did in Hindi film music!). But in Bengali adhunik (modern) songs, which were released in Durga Puja albums year after year, Pancham kept on experimenting with different themes and sounds with aplomb, and was helped in no mean measure by the great singer Asha Bhosle. Initially, Pancham’s Bangla songs were penned by writers such as Sachin Bhowmick, Mukul Dutta, and the great Gouri Prasanna Majumdar; but later, most of his Bangla songs were written by his associate Swapan Chakravarty.

Nodir Paare Uthchhey Dhowan is a song released in the Puja album Phire Elam in 1986. It was written by Swapan Chakravarty, and sung by Pancham himself.

A truly formless, path-breaking song!

Nodir Paare Uthchhey Dhowan Mone Hoy Kichhu Hoyechhey

Jaar Laagi Aami Boiragi Hoyechhi, Hoyto Ba Shei Jolchhey

[I learned only recently that the first two lines are translated from traditional Sufi poetry.]

The song starts with drum beats, the ”whoosh” sounds of the breeze, and some weird “flanging” effects to create an atmosphere of eeriness, emptiness…followed by a heart-wrenching, wailing alaap by Pancham. Going by the alaap, one would expect a slow, raga-based bandish. In fact, the first two lines are exactly that…even though Pancham employs a bit of yodeling in the proceedings – is that totally unexpected? No, as the break in his voice is nothing but his sound of anguish…his pain. Here, Pancham strides a bit into the tappa style of singing, or is it a bit of Sufiyana, or both? There is also this incessant strumming of the same, melancholic note on the guitar played like the Baul’s ektara, which evokes a trance-like effect in the listeners’ mind – the trance that usually accompanies emptiness, numbness, loss. You start visualizing the banks of a river, a lonely boat on it, and perhaps a boatman who is singing the pain of the protagonist (who might actually be the boatman himself). Pancham sings of “smoke” rising from the other side of the river – which, figuratively, is probably because of the “burning” of his beloved! Probably she too is in pain – only probably (“hoyto ba shei jolchhey”), because he is not quite sure…. Noteworthy is the way he sings “dhowan-ah,” with that Panchami throw (as I name that effect), getting into the Bhatiyali terrain – good Lord, what could he not do! At the end of the first line, the vibrating flute does its part of adding to the feeling of loss. Also worth studying is the way the words are stressed upon the second time they are sung: “Jaar Laagi Aami Boiragi Hoyechhi” (for whose sake I renounced the world) – is that anger? Is he then a victim of betrayal? Perhaps the next set of words will solve the mystery…

Kotha Diyechhile Tumi Je More

Thakbe Ogo Tumi Amaari Saathey

Tobe Keno Haaye Tumi Doore Chole Gele

Amaake Bhuliye Tumi Ki Pele

Kotha Diyechhile Tumi Je More…

Trust Pancham to do the unexpected. Just when you gear toward settling down to the slow pace of the prelude, Pancham plays out his next magic trick. He breaks the structure of the song and settles very comfortably into a fast-paced ditty, with the tabla for good company. [Note, the tune of this part of the song is the tune Pancham used to create the Lata Mangeshkar mujra “lo saahib phir” from the Hindi film Maati Maangey Khoon.] The words make it clear that he is a victim of betrayal… as he says, “You had promised to stay with me forever, yet you left me and went away…Why? What did you gain by forgetting me?” Notice the way he stretches the word “ogo,” which gives a feeling of yearning, the type of persuasive call one usually reserves for loved ones. Listen to the tabla here…suits the pace of the singing and also does justice to the complaining tone of this part of the song, as though adding to the nagging!

Khoiri Ronger Maati, oi Khoiri Ronger Maati

Rod Chhilo Shukno Chhilo Phete Jawa Maati

Borsha Ritu Elo, Oi Dekho Borsha Ritu Elo,

Maati Bheja Gondho Elo, Sobujer Chhowan Elo

Eka Ki Tumi Daariyechhile Aamio Chhilam Eka…Eka…Eka

Tai Dekhe Deke Uthechhilo Kuku Kuhu Keka

Aar Tai Shune Aamraa Dujon Haathey Haath Rakhi

Tumi Amaar Mon Rangiye, Mon Rangiye Dile

Ho, Kotha Diyechhile…

Yet, once again, Pancham returns to the sad, monotonous, one-note strumming, almost as though returning to tug at the listeners’ heart strings! Pancham is in contemplative mood now…thinking of the past and imagining the present.

The lyrics need special mention. The simple words and Pancham’s sounds create the perfect atmosphere for a broken heart that simmers in pain. He sings about the red-brown “maati” (most probably referring to the lateritic soil of a village in Bengal), which would be dry and cracked (“phete jawa maati”) by the strong sun (“rod chhilo shukno chhilo”) Or, is he referring to his life before her – dry and parched like the summer earth? . The way he stresses certain words: “khoiri ronger maati,” for example, is worth noticing. Is it because he is now singing of hard soil, parched in summer, that he places a strong, perhaps even harsh, stress on the term?

The mood changes…as does the season. The experience now borders on the surreal. Pancham suddenly softens… and lovingly announces the arrival of the rain (“borsha ritu elo”) and probably of her in his life, stretching the word “elo,” probably to wait for the rain to become steady (the sound of thunder and rainfall accompany this part)! He sings about the smell of wet soil (“maati-bheja gondho elo”), and the return of the greens (“sobujer o chhowan elo”) in his life. Worth mentioning is the way he mellows down to sing of the smells of “bheja maati,” (“maati” sung differently now; the bitterness nearly gone) and “sobujer chhowan” – does he hope things to turn around for him and his beloved with the turn of the season? Or is he thinking of the past when he had her by his side? He seems to travel back and forth in time: he thinks about her in the past, standing (and waiting for him?), and he imagines the two of them holding hands while listening in glee to the lovely calls of the koel (“kuhu”) and the peacock (“keka”). He also sings about how she has (or had?) won him over (“mon rangiye dile”). The words here provide a slight hint of hallucination – past and present together. Masterful rendition this!

I cannot end the essay without mentioning the superb sound effects employed by Pancham in this part of the song. A technical Master at work: the torturous loneliness highlighted by the echo “eka…eka…eka,” plus the sounds of thunder and rain, and the birds chirping their way from one speaker to the other! The song ends with the magical sounds that started it – the strings strumming that monotonous, melancholic note.

Pancham’s vocals do justice to this genre of songs. His is a simple, earthy rendition, which takes a seemingly simple, sad song of love to heights of musical excellence. A quality he inherited from his illustrious father, I am sure. The feeling of loss is so brilliantly portrayed that one can actually visualize the loneliness of the singer…singing an ode to all such “love-failed” people!

Atanu Raychaudhuri

panchammagic.org