Meri Nazar Hai Tujhpe …

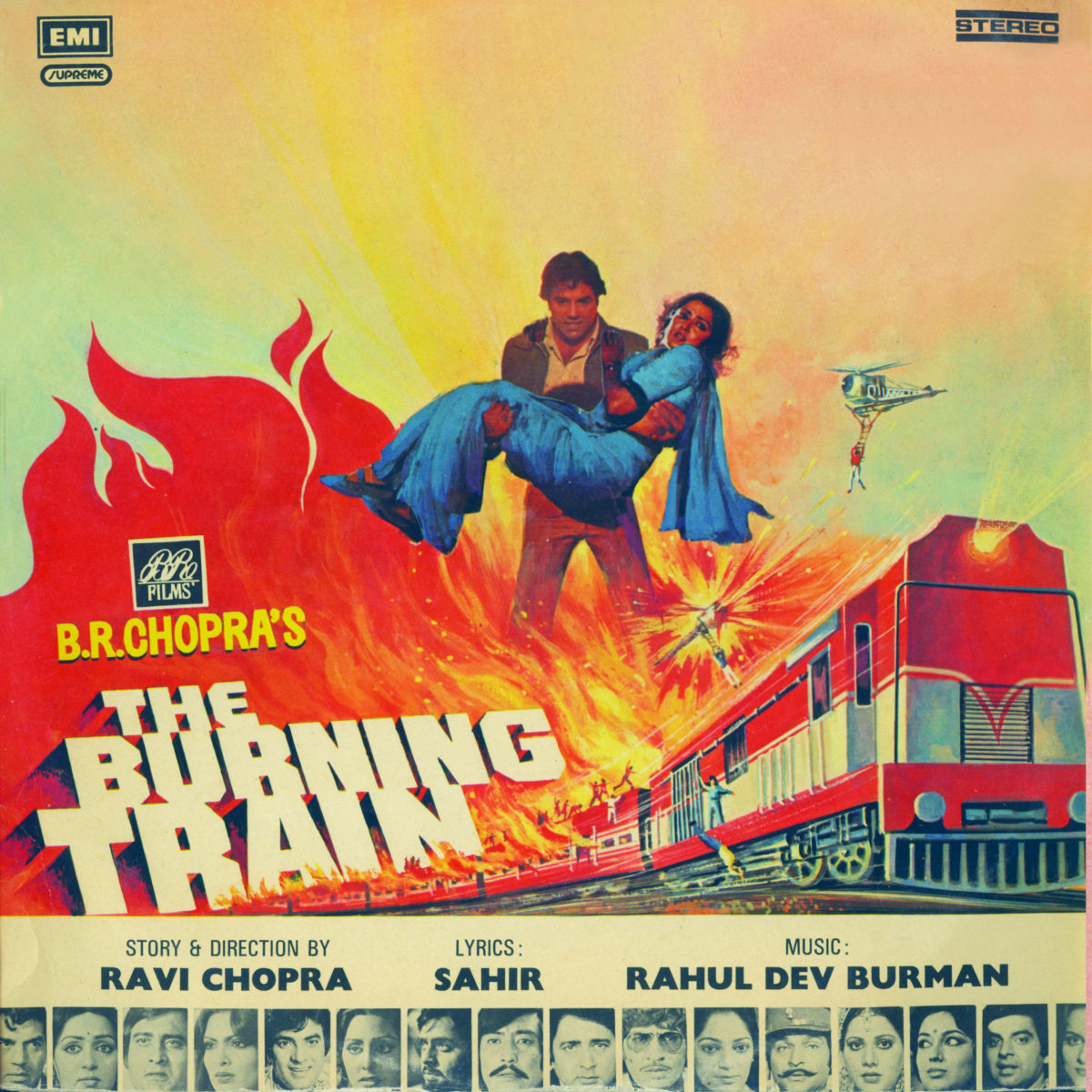

Film: The Burning Train (1980)

Producer: B. R. Chopra

Director: Ravi Chopra

Lyrics : Sahir

Singer: Asha Bhosale

–

R D Burman and Sahir collaborated on very few films: Aa Gale Lag Jaa, Joshila, Deewar and The Burning Train (the film from which our song for this fortnight comes). The multi-starrer was doomed (ironically) to a box-office fate not unlike its genre. The soundtrack deserved a better fate and boasted a qawaalii, a ghazal, a devotional song arranged like a church hymn, and the requisite.

The song for the fortnight, merii nazar hai tujhape, showcases RDB’s flair for using overlapping percussive elements to decorate simple melodic lines in the song. What augments this effort is a fusion between western and Indian classical styles, which provides enough hints about what the song might look like on screen (an East/West fusion dance performance featuring Hema Malini and Parveen Babi).

Set primarily in Abminor in standard tuning (and liberally exploiting the natural harmonic and melodic variants), the song opens with a flourish of brass after which violins backed by chord strums on an acoustic guitar join in. A drum roll marks the end of this fragment as the bass guitar tumbles in overlapping percussion spliced across the left (claves) and right channels (hi-hat) complement off-beat chord stabs on the synthesizer. The string section joins with three-note-fragments starting on the second count of each measure. The chord strums continue on the acoustic guitar. A short solo phrase is up next on the electric guitar with the brass providing a resounding response at the end of it. The brass section launches into a four measure contribution, before a percussive improvisation section featuring, among other things, the bass guitar, a shaker, congas, the hi-hat and the triangle. As if this was not enough, RDB now throws in the South Indian element by introducing the mridangam, which then proceeds to accompany phrases played out on the sitar. The return to the western element isn’t too far away as the next segment features melodic phrases and chords played out on an acoustic guitar while another acoustic guitar provides constant strums of chords. The trumpet replaces the first acoustic guitar for the coda of the prelude as the bass guitar punctuates the measures. The off-beat synthesizer stabs return with the shaker and the acoustic guitar to provide the rhythm introducing the song.

The muKa.Daa proceeds at about one-fourth the frenzy of the prelude; it’s more laid-back and the rhythm section features the conga, the hi-hat and the acoustic guitar, with the standard string section backing. As Asha is all set to return to the muKa.Daa, the conga provides the turnaround taking us back into the western section.

The a short phrase on the sitar serves as a bridge from this western fragment of the muKa.Daa to its “eastern” tail. Asha’s vocals are backed by a comfortable combination of tabalaa and ghu.Ngharuu, but the string section continues to provide backing and the chords on the acoustic guitar continue.

The first interlude revisits a fragment from the prelude (off-beat chord stabs on the synthesizer with three-note-fragments starting on the second count of each measure from the string section) but minus all the fancy percussion. The eastern element returns with gentle phrases played out on the sitar accompanied by the tabalaa and the acoustic guitar; and more flourishes from the string section mark the end of this fragment and the beginning of the a.ntaraa

The rhythm section on the a.ntaraa continues to comprise the tabalaa, the acoustic guitar and the bass guitar with fills from the string section. The a.ntaraa ends by revisiting the eastern tail of the muKa.Daa before quoting the first line once again.

The return to the western is only brief as the second interlude begins. This begins with interplay between the eastern and western rhythmic components. First, the tabalaa and the mirdangam trade phrases with the ghu.Ngharuu embellishing each contribution. The mirdangam then trades licks with the drum (an interesting mix of hi-hat snatches and brush runs). The flute enters to trade melodic fare with the sitar as the ghu.Ngharuu and mridangam provide rhythmic backing. The western element returns with a blast (literally!) from the brass section. The string section joins to trade phrases as the shaker, bass and conga provide furious backing. This portion also marks a clever (temporary) switch to a major key (Bb) with the closing fragment marking a return to the original key for the second a.ntaraa, which follows the laid-back style of the muKa.Daa.

As Asha returns to the muKa.Daa and finishes things off in the western element, the completely instrumental coda ensues. A combination of synthesizer chords, drums, bass guitar and electric guitar trade licks with the mridangam backing a phased lick from the electric guitar. The mridangam and bass guitar then take centre-stage before the sitar joins in. The brass section joins in to bring things to a close.

Lyrically, the song doesn’t offer much to dwell on. The words are simple (except, perhaps, for dafaatan, which drops in like Kushabaash in aanewaalaa pal), there aren’t too many complex ideas. For better or worse, that lets you focus on everything that RDB decided to toss into the composition. He seems to have had fun doing it, and some of that hopefully wears off onto the listener.

George Thomas

Panchammagic.Org